Renato Cisneros (born January 12, 1976) – Peruvian novelist, poet - You Shall Leave Your Land (2017)

Read about the author's novel/memoir The Distance Between Us here and here

Cisneros talks about his novel La distancia que nos separa / The Distance Between Us here (in Spanish)

Read an excerpt from You Shall Leave Your Land

Ferenc Molnár (originally Ferenc Neumann) (born January 12, 1878) – Hungarian novelist, playwright – The Play at the Castle

Read about Molnar here

(The Café Society of Ferenc Molnár)

He observed Molnár taking off his slippers and placing them by his bed, the one facing the other, toe-to-toe. The visitor inquired the meaning of this ritual.

“You see,” Molnár replied, “if you put them side by side, both staring straight ahead, they look like a married couple who have just had words. It depresses me. But see how friendly they look nose to nose! They cheer me up and I sleep better.”

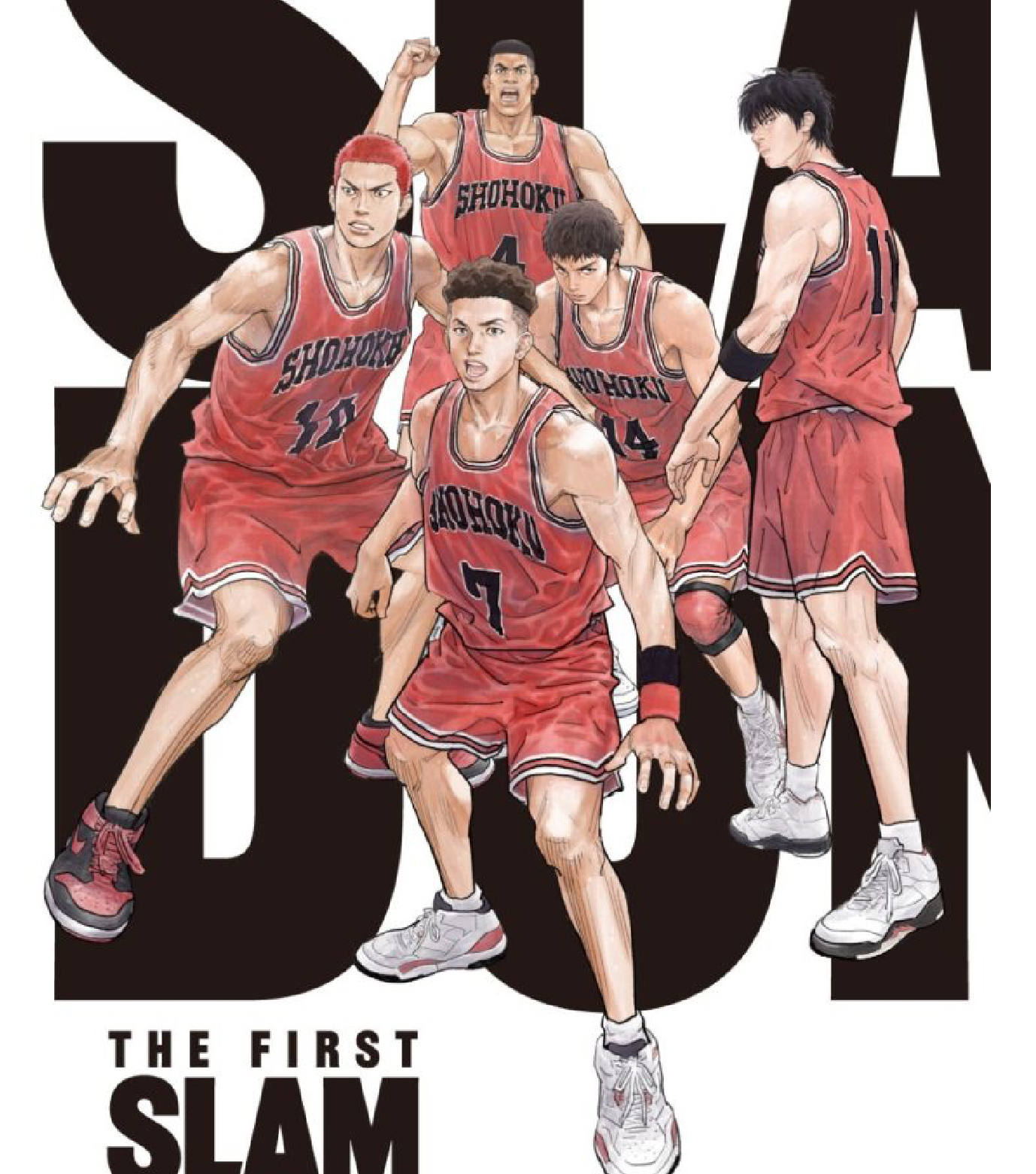

Inoue Takehiko (born January 12 1967) – Japanese manga artist

See examples of Inoue Takehiko's art from the 2009

"The Last Manga" exhibit

The Last Manga Exhibition - complete catalog

Read an interview with Inoue Takehiko here

Visit the Inoue Takehiko official website

https://itplanning.co.jp/home-en/inoue

Haruki Murakami (村上 春樹) (born January 12, 1949) – Japanese novelist – Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (2015)

Read an interview of Murakami in the Guardian

Tsukuru Tazaki, as the author calls his own novel for short [Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage], sold a million copies in two weeks when it came out last summer in Japan. (Murakami was born in Kyoto to two literature teachers, and grew up in the port city of Kobe. These days he lives near Tokyo, having spent periods in Greece, at Princeton and Tufts universities – where he wrote his masterpiece, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle– and recently in Hawaii.)

Murakami has often spoken of the theme of two dimensions, or realities, in his work: a normal, beautifully evoked everyday world, and a weirder supernatural realm, which may be accessed by sitting at the bottom of a well (as does the hero of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, or by taking the wrong emergency staircase off a city expressway (as in 1Q84). Sometimes dreams act as portals between these realities.

Read about Murakami's writing style in this 2014

Atlantic article

"The Mystery of Murakami - His sentences can be awful, his plots are formulaic—yet his novels mesmerize"

Page after page, we are confronted with the riddle that is Murakami's prose. No great writer writes as many bad sentences as Murakami does. His crimes include awkward construction ("Just as he appreciated Sara’s appearance, he also enjoyed the way she dressed”); cliché addiction (from a single, paragraph-long character description: “He really hustled on the field … He wasn’t good at buckling down … He always looked people straight in the eye, spoke in a clear, strong voice, and had an amazing appetite … He was a good listener and a born leader”); and lazy repetition (“Sara gazed at his face for some time before speaking,” followed shortly by “Sara gazed at Tsukuru for a time before she spoke”). The dialogue is often robotic, if charmingly so.

Murakami’s impoverished language situates us in a realm of utter banality, a simplified black-and-white world in which everything is as it appears. When, inevitably, we pass through a wormhole into an uncanny dimension of fantasy and chaos, the contrast is unnerving.

Murakami writes genre fiction—formulaic, conventional, with an emphasis on plot. But it is a genre that he has invented himself, drawing elements from fantasy, noir, horror, sci-fi, and the genre we call “literary fiction.” The other ingredient, which we tend to think of as antithetical to genre fiction, is a hostility to tidy resolution.