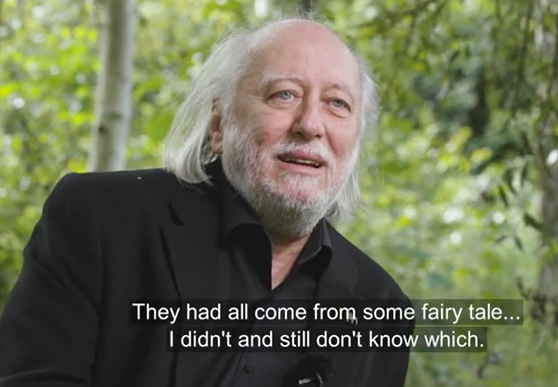

László Krasznahorkai (born January 5, 1954) - Hungarian novelist, screenwriter

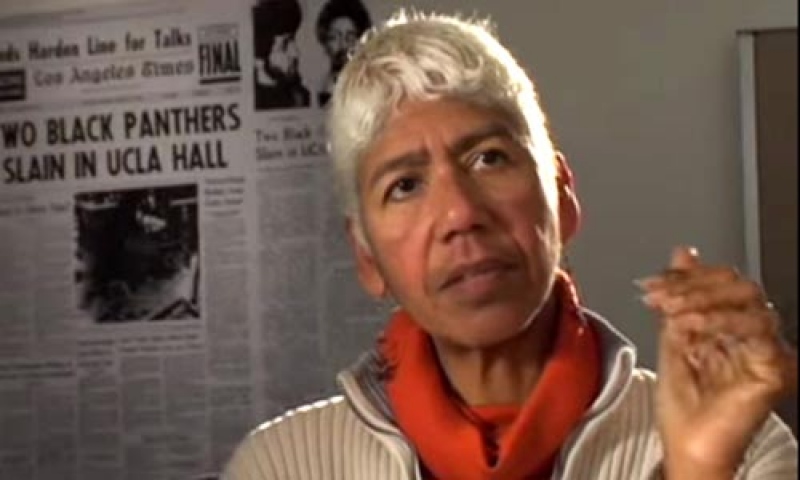

Ericka Huggins (born January 5, 1948) - US writer, poet and human rights activist

Visit the website of Ericka Huggins

Ngugi wa Thiong’o (born January 5, 1938) - Kenyan novelist - The Perfect Nine (2019; 2020 English transation)

Read about Ngugi here

Watch Ngugi speak about writing in African language

Hayao Miyazaki 宮崎 駿, Miyazaki Hayao (born January 5, 1941) - Japanese manga, film animation artist, film director/producer - Howl's Moving Castle (2004)

Read the IMDB biography of Hayao Miyazaki.

Watch Miyazaki speak about his work (2009 Comic Con with John Lasseter of Pixar Studios)

Umberto Eco (born January 5, 1932) - Italian novelist, essayist - The Name of the Rose (1980)

Read Umberto Eco's obituary in the New York Times and the Guardian

Read about Eco's literary legacy in this 2016 Guardian article

Eco’s first, watershed novel, The Name of the Rose, was published in 1980. An artful reworking of Conan Doyle, with Sherlock Holmes transplanted to 14th-century Italy, the book’s baggage of arcane erudition was designed to flatter the average reader’s intelligence.

Yet the success of The Name of the Rose weighed heavily on Eco. When the French director Jean-Jacques Annaud released his film of the novel in 1986, Eco refused to speak to the newspapers about it. Each night when he returned to his flat in Milan he said he could “barely open the door” for the accumulation of interview requests. In private, Eco judged Annaud’s film a travesty of his novel, and found the monks (apart from the one played by Connery) “too grotesque-looking”. Yet Eco approved of Annaud’s Piranesi-like sets, which he concurred were “marvellous”.

His second novel, Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), was a thriller set amid shadowy cabals and conventicles such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Rosicrucian Society. Eco saw modern-day political parallels with these and other sects; indeed, the P2 masonic lodge and the far-left fringe of the Red Brigades indulged a similar secrecy and fanaticism. Eco was fond of the Italian term dietrologia, which translates, not very happily, into “behindology” and presumes that secret cliques, camarillas and consortia are everywhere manipulating political scandals. In all his work, fiction and non-fiction, Eco displayed a classically Italian enthusiasm for conspiracy and arcana.

In 1971, Eco became the first professor of semiotics at Bologna, Europe’s oldest university. His lectures at the university, avidly attended by semioticians, analysed the James Bond novels, the Mad comic magazines and, with equal fizz-bang, photographs of Marilyn Monroe. Throughout his Bologna professorship, Eco denied that he was “intellectually slumming it” by speaking of Donatello’s David in the same breath as, say, plastic garden furniture.

When the entire world is a web of signs, he said, everything cries out for exegesis. Marginal manifestations of culture should not be ignored, he explained: in the 19th century, Telemann was considered a far greater composer than Bach; by the same token, in 200 years, Picasso may be thought inferior to Coca Cola commercials. (And who knows, Eco added jokingly, one day we may consider The Name of the Rose inferior to the potboilers of Harold Robbins.)

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/feb/20/umberto-eco-obituary

Umberto Eco speaks about words and the semiotics of translation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYMCy8gEhog

Umberto Eco [Minute 10:20]: Should a translation lead the reader to understand the linguistic and cultural universe of the source text, or transform the original by adapting it to the reader's cultural and linguistic universe?

The question is not as preposterous as it seems when we consider that translations age. Shakespearean English is always the same, but even if modern Italian readers read Shakespeare in an Italian translation of the 19th century, we feel uncomfortable.